Revolutions, Depressions, It’s All In Our Heads

In September 2008 the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. marked the popular beginning of the late recession (2008 – Today). This is probably no news to anybody in the developed world: to many this meant the loss of their homes, loss of their jobs, their businesses and for the lucky ones it meant at least a dent in their life stile.

But why? There is more wealth in this world today that it had ever been on Earth. Of course this wealth is not evenly distributed but in this post I am talking about us, the western civilization, a world in a world, so wealthy that it feels like a sin to talk about hardship. Just a few hundred years ago, a handful of generations, our forerunners lived a very different life: there was no electricity, no clean water, no refrigerators, very few people took vacations and giving birth was probably the riskiest business in the world, with a mortality rate of 30% (that’s one in three). Average lifespan was so low that more than half of the today’s population (3,500,000,000 people) should be dead by the same standards and there were no smart phones. By comparison, today, we have toilets, sanitation, vaccines, antibiotics, MRI machines and incredible medical care in general, we can read and write we have access to all the knowledge in the world, we have swimming pools of drinking water, incredible food, instant communication and we can fly… We even have smart phones. Personally, I think we’ve got pretty much everything … So again, why is there a crises?

I am not picking on smart-phones. As an IT guy I believe they are a wonderful technology, I just found it intriguing that when they asked Dr. Jack Lewis, Presenter of “The Tech Show” on Discovery Channel “What the most important piece of technology in his life was” he answered “Without a doubt my smart phone”. I find his attitude very interesting in the context of this discussion, especially coming from a person of his background and spoken in the promotional material of a show done by a TV Channel with such a high rating. If people in these circles (PhD and stuff) think like that, it kind of hints to why we complain so much and perhaps a little bit to what this crises is really about.

Revolution

Everybody in the developed world has probably heard about the industrial revolution. It is still a debate among historians whether it really was a revolution, considering that it happened over a long period of time (100 years or so), but what it did was to liberate people from the day to day struggle of a subsistent survival, by ways of machines which greatly increased people’s ability to produce food and housing and gave them the gift of “reserves”. Mentioning this might seem weird today, but back then, people could barely produce as much as they consumed. Work was extremely demanding and brute work fore was the only solution. In many societies child labor was a regular and often necessary practice and having children was the way to acquire this resource. The lack of reserves meant that if a very dry year hit agriculture, they didn’t just have a rise in the cost of bread, it meant that hundreds of thousands of people died of malnutrition the year after. Reserves are an extremely important aspect of our existence. We don’t realize it’s necessity because we have it and we use it to buffer our “down periods”. Like oxygen, it is not noticeable until one runs out of it, so one can imagine what an enormous revolution this was to humans. It completely changed the way we approached life. Take just one example: back then, people did not have the concept or cultural need to have something like “pension” (a period when one doesn’t have to work but lives off their “reserves”). Beyond the fact that people lived very short lives (about 35 years on average), the cultural norm was that one worked as long as one was able to and if it happened that one could work no longer because of an injury or disease and did not have the luck of a family with the potential to care for him, the outlook was not bright.

An interesting effect of the industrial revolution was the so called Jevons paradox, named after William Stanley Jevons who observed that contrary to intuition, increased efficiency in the usage of a resource, does not reduce the usage of that particular resource but on contrary it increases it. The explanation is relatively simple: because of the increased efficiency and thus reduced cost of operation, even those industries can afford it now that were not able to do so beforehand. As a consequence, although a particular unit will be more efficient and consume less resources, there will be a lot more units in use and so there will be more resources consumed per total. So if we think about it a little more deeply we can realize that this effect is no paradox at all. It only is one (as so many other paradoxes) when one takes into consideration an isolated case in a non isolated environment.

The “social” has not escaped Jevons’ paradox either, or a slightly twisted version of it. Even deep into the industrial revolution, the vast majority of people did not start feeling the benefits of it but rather they continued to live a very similar miserable life. Increased efficiency led to more food, which led to increased population (natality stayed constant but mortality dropped), which meant more children. But instead of abolishing child labor, factory owners realized that this was a very cheap and plentiful resource (factory owners had to pay around 1/2 for a child as compared to an adult yet the work almost as much as an adult), so as a result child labor became even more widespread. So did other kinds of exploitations (a 16 hour work day, 6 days a week was a regular working schedule, 96 hours a week) resulting in ever greater production of goods but with no change in the lifestyle of the population.

It took a very different kind of revolution to change that, a spiritual revolution. One in which people realized that all goods in the world are useless if they don’t make the life of people better but this was a very hard process. Although the technological change was brought in by the stringent need to make life better and the relentless acquiring of knowledge, it made no improvement on people’s lives because people did not know how to embrace it. They did not have the concept of a life without the day to day struggle so they continued on working or demanding others to work the same way as they did before. It took nearly a hundred years, from the onset of the revolution, for people to recognize the possibility and need to change this aspect of their life.

Constant Progress, Exponential Result

In mathematics, a geometrical progression is sequence of numbers (i.e. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …) that are connected with each-other in such way that every number after the first number is found by multiplying the previous number with a non zero number called a common ratio. For example, in the progression (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 1024, ..) the number Xn is found by the formula X(n) = 2*X(n – 1) like (2 = 2*1, 4 = 2*2, …, 64 = 2*32, …, and so on). I deliberately picked this progression because it is similar with Moore’s law (the one that say that computer chips power is doubling every 18 months, in a nutshell) and so it is easy to associate with what we call exponential growth, but in essence, all these progressions share a particularity: growth in the beginning is small, but then it becomes ever faster until at some point it becomes insane (in the example above, after just a hundred iterations the number becomes 12 600 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 something on the order of all the estimated atoms in the universe). This rate of increase depends on the common ratio, the bigger it is the quicker things get out of hand.

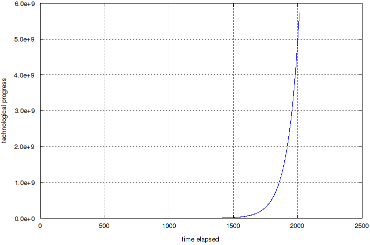

This same system can easily be extrapolated (although with great simplification) to technological progress in general. After all, what we do is to take our knowledge and multiply it by putting in some effort so we end up with more and then repeat the process. Logic dictates that if we take into consideration all technology in general and a longer period of time, we need to pick a much smaller common ratio (rate of progress). So for this thought experiment, I picket a period of 2012 years and a rate of progress of 9/8.9 (which means that we know approximately 1.0011 times more this year than we knew last year). If we plot the evolution of our knowledge over these 2012 years (considering that we knew exactly 1 at the time we started counting time), we get what is in the picture on the right. We can see that for nearly 1500 years our progress was very small (by comparison), but than between 1500 and 1750 it picked up and than skyrocketed after 1750. The graphic is in fact very representative of how we see progress. The rate of growth was not small, in fact it doubles every 125 years but the same way we don’t see any progress till around 1500 on this graphic, we don’t see it in our history either. The magnitude of the final value, eclipses all but the very end of the period.

Personally, I don’t think there was an industrial revolution at all. I believe what we see as the period of our industrial revolution is nothing more than the equivalent of the section between 1500 and 1750 in the graphic above. The period that we started to see significant increase in technology over a relatively short period of time, but the progression has been more or less constant throughout of history. It is just our perception that changes. We picked the steam engine because we found its invention to be in this period and we made it the culprit our industrial revolution, but in my opinion it was no more revolutionary than fire was, or the invention of the wheel, or that of writing or mathematics, and so on, it’s just that those inventions multiplied a much smaller volume of knowledge ending up bringing a smaller progress.

The real revolution here is the human spirit, which is the common ratio in this progression, the force that drives this monumental machine. Unfortunately, this driver is not perfect and if we don’t recognize the faulty pieces and correct them, I believe we are heading into enormous trouble.

Legging Behind

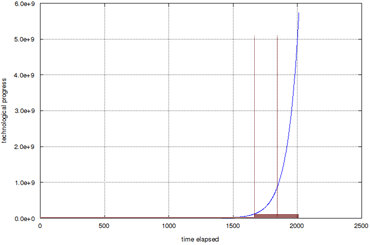

If we superimpose the period what we call industrial revolution over this graphic (it won’t be exact but it doesn’t matter for the intent of this conversation) we can see that it took us nearly a hundred years (approximately 1/3 of the period between the date we pinned as the start of the revolution and today) to realize that a big change is taking place and we need to adapt to the situation, spiritually (mentally) speaking. By than we already see a great deal of progress (approximately 10 fold), progress which becomes incompatible with the old ways (culture and mental together) and prompts the change which brings us, spiritually and culturally in step with technology (more or less) but then again nothing really happens in this domain till today.

The two vertical red lines split the period since the beginning of the industrial revolution and today in three parts. The horizontal red blocks represent the way the cultural in relation with the technological progress. This is basically a line all the way to the end of the first third of this period, following neatly in step with technology but then the lines diverge when technology picks up and leg appears. This discrepancy lasts until the first third of the period, the moment we updated culturally to catch up with technology and the two lines meet again. I’ll cal this Mo (Moment zero).

Technology however keeps on progressing in its relentless geometric progression but our culture and social structure remain approximately at the same level even today. The political, economic and bureaucratic systems are the same as they were then. So is social hierarchy, the relation between employer and employee, currencies change but we base our value system (gold in the national treasury), we cherish the same property system and we see our progress purely in the context of a growth system that equates consumption of products.

You might be tempted to say that surely there must be something wrong with that picture. We cannot be so far behind culturally as seen there. Interestingly though it is quite the contrary: the technological progress of 2012 (as seen in this graphic) is only about a hundred fold that of the progress at (Mo, moment of last cultural update) but in reality our progress is more like a ten thousand, or maybe a hundred thousand fold (I mean, how much progress do you think there is between the steam engine and the ion drive that takes space probes to the edge of the solar system, or how much progress is between a herbal tree that maybe fixed an upset stomach and a genetically engineered virus that cures a degenerative hereditary disease). I deliberately chose a smaller growth in my example so that I can represent the cultural progress with more than just a thin line). In reality the discrepancy is thousands of times bigger.

Old Problems, Modern Paradoxes

The period we call the industrial revolution presented people with a never before encountered problem. The technological progress they were making jumped ahead the society and created a conflict due to people’s inability to quickly adapt. You can imagine the desperation of industry owners when they realized that they need to give up child labor, having to pay double wages to adults, when they heard that they need to reduce working hours and loose money there as well… Imagine how difficult it must have been to parents who had lots of kids to be told that their kids can no longer work and thus they need to give up all the income that was coming that way. These are very natural things today (even revolting to talk about them) but by the standards of those days these were natural worries. It must have been a genuine social crises. An enormous conflict between visionaries and conservatives or those that were just simply afraid that the change will destroy their livelihood, all feeling the pressure and necessity of change under the new conditions but not knowing what the exact path was. Change was not easy, but it had to happen eventually and contrary to intuition in those days, the cut to the 8 hours work, the raise in salaries, improvement of working condition, abolition of child labor and many other “costly actions” actually raised productivity and ultimately made more profit rather than reducing it. We now had a modern society capable of fully benefiting from all the technological advancements of the day.

But history repeats itself. Today, this renewed incompatibility between the technology and our ways of life raises some incredible paradoxes of it own, which in my opinion are impossible to solve unless we do some extremely radical changes in our way of lives. I would like to emphasize just two of them, the ones that I find most representative.

To create a new product, a company, must invest in research and development, a process which is both lengthy and costly and on the top of it is uncertain (not all products actually make the market or are accepted by the market). So essentially what a company does is it takes its reserves or a loan, invest it in the research, builds a new product and then sells enough units to recover the investment and make a profit, which than they can reinvest into the next generation of products. This process used be be a very comfortable one, companies had years to sell a good product giving them time to recoup the investment. Lately however, competition and the ever faster rate of technological advancement companies find themselves in the situation where there is not enough time to sell units to recoup the investment necessary for its development. So to avoid certain death, companies pursue two tactics, one is to push people into throwing away the old (often one year old) device and buy a new one, or the second one is to delay technological development to have enough time to sell by forming into oligarchic organizations or by killing competition with law suits or buying them out. Neither case actually deals with the problem, they just postpone them.

Another enormously burdening paradox is that with each new tool that we invent, we eliminate more and more the need for manpower. Normally, this should be good news, because we could work less, and live easier lives, but the social order that we live in does not allow us to do so. We are culturally stuck in a capitalist world where the mantra is “gain more capital” and for that we “work”, we cannot even contemplate not to work, some of us work two jobs others work at home even in weekends (I do) and we cannot relinquish some of that “gain” which comes as exchange for our “work”. It feels like a religion. Just as our ancestors continued sending their kids to work and worked themselves 16 hours a day many years into the industrial revolution, so are we stuck with working as much as we can, often fighting for the possibility to do so.

Crises

No wonder we see this as a crises, we are incompatible with the world we live in. We created the change, the advancements, but we cannot accept them. We fight and struggle against it and try to impose on it the way of life we are so used to, but it’s not possible any more. It’s like a shock wave that’s pushing through a matter at speeds that are no longer compatible with that matter. Sooner or later will bang.

The Lehman Brothers Holding did not spark any depression, nor did the the housing boom or the raise of unemployment. These are all effects, not causes. But in my mind, just like there is no such thing as an industrial revolution, but rather just an accumulation of advancements that suddenly became noticeable, there is no crises either. What we have here is an accumulation of incompatibilities that suddenly became noticeable and impossible to postpone. They appeared almost immediately after the Mo point, when technology and culture started to diverge once more but we fixed them by postponing them and now there all here, at once and we need to deal with them.

We haven’t changed our ways for too long and now it’s not going to be easy. We have evolved, we are better prepared but the small offset that appeared during the industrial revolution was nothing compared to what we are facing now, but I believe there is hope. I believe that the changes we will adopt, as scary as they may be, will eventually help us, just as they helped our ancestors during the industrial revolution. I am not entirely sure what the right course is. I do have ideas but they are convoluted and not coherent. Many things need to be changed but the trick is we have to make the right ones and there is no right or wrong guide here just hints.

Thanks for reading. If you care to comment I would really like to hear about it. If you have ideas of your own and care to share them that’s even better. Maybe we can even spark a discussion.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.